The Blankenship criminal case and the history

of coal-industry rule in Appalachia

I finished a first draft of Carla Rising in April 2010, just as we received news of a deadly mine disaster in Raleigh County, West Virginia. The accident at the Upper Big Branch mine killed 29 men working about 300 meters (1,000 feet) underground.

Four years later, a federal jury convicted Don Blankenship, chairman of the company that ran the mine, with conspiracy to violate US mine safety and health regulations in relation to the disaster.

As a newspaper reporter, I used to write stories on political corruption cases that came before federal judges in Southern West Virginia, where Blankenship is currently on trial. (I’ve also written a nonfiction book dealing with the state’s long history of coal-influenced politics, a central theme in Carla Rising.)

I’ve been talking to other journalists about the Blankenship case. As a former reporter in West Virginia, what is interesting to me is that — for the first time that I can remember — the federal government went after a powerful, anti-union coal company chairman (and donor to right-wing causes), as opposed to targeting unions (as they did before 1935) or targeting corrupt state and local government officials who’ve allowed energy companies to break the law (as prosecutors charged in cases after 1970).

Over a number of years, reporting and reading stories like these in West Virginia can make a person increasingly cynical. In a word, it got harder to sort out life-threatening environmental and workplace offenses and financial crimes from business as usual.

This is one of the stories I wanted to bring out in Carla Rising: How coal companies have gotten away with intimidation, abuse and murder in the bad-old days of “King Coal.” Those who’ve worked to bring reform to the system, on the other hand — workers and many others — have been cast as “Communists,” “radicals,” (or, more recently, merely “liberals” and “anti-coal”) for standing against clearly exploitive and unjust practices by coal companies, long aided by state and local political leaders who are almost always beholden to them.

“Breaking the law” doesn’t begin to describe the offenses of 20th-century energy firms against workers and the public in Appalachia. Again and again, coal companies operating in that region have proven that they ARE the law. In 1990, I covered the conviction of Governor Arch Moore, who pleaded guilty to exchanging money and political favors with a big coal firm. The practice goes back more than 100 years, when the region’s most influential railroad and coal barons held powerful public offices themselves.

When I lived in West Virginia, I wrote a number of magazine articles about the notorious 1920 shooting in the independent (non-company) town of Matewan. More than 20 pro-union men were tried for the killings of seven company detectives. In looking at the trial transcripts — and, again, as someone who had covered modern court cases — I was amazed at the role played by the private police agency run by Thomas Felts, the brother of two of the victims. I was struck by the fact that Tom Felts actually had a seat at the prosecutors’ table, where he helped manage the prosecution’s witnesses and evidence, much of it gathered by his own men, who were sometimes officially recognized as police officers. Here, at this trial, the line between the private company and the state was certainly blurred.

This was central to the notorious labor conflicts of that time: Before union miners picked up guns, they were trying to use the courts and appealing to Congress to fight unjust and total corporate power over democratic institutions in the state. More often than not, the miners and their union were outmatched. In repeated cases — most notably the US Supreme Court’s 1917 Hitchman decision — federal authorities refused or were unable to intervene in coal labor issues, setting up the dangerous conflict that drew US Army involvement in 1921. (See Carla Rising, pp 157-165; 298-300.)*

Two years after the US Supreme Court ruled on the ultimately unconstitutional Hitchman — an especially “bad law,” supporting injunctions and arrests of organizers just for “talking union” — the West Virginia governor established the state police department, empowered to intervene, militarily, on the side of industry against labor organizers and strikes. (See Carla Rising pp 104-108.) It was also the Hitchman ruling, more than any other, that empowered the US president to send 2,500 Army troops and a squadron of bombing planes. All this, to put down the coal miners’ massive march to Logan, where they hoped to free their friends who’d been arrested — sometimes without charges — jailed for little more than siding with the union. (See Carla Rising, pp 75-77; 264-68.)**

The first 30 years of the 20th century likely saw the worst abuses of “King Coal.” Writing in The Nation in 1920, Arthur Gleason tells us of how Logan County police monitored roads and railway stations, stopping almost any stranger getting off the train to ask his business in Logan, making sure no union men could enter and talk to miners. Once, Gleason says, County Sheriff Don Chafin (the model for Riley Gore in Carla Rising) abducted and beat the leader of a fraternal group, the Knights of Pythias, upon mis-understanding that the man had come as an “organizer.”

During that time, there were countless peonage cases brought against coal companies by national human rights organizations. In 1906, West Virginia Gov. William Dawson was informed that the Italian Embassy was registering complaints with the US Secretary of State regarding the treatment of Italian citizens in the Mountain State — men being forced to work in the mines at gunpoint. (See Carla Rising, pp 170-74.) Complete company control of the mining camps had kept these men from sending word to loved ones, informing them of their virtual captivity, or even being able to afford a railroad ticket out of the camp.

Remarkably, many of these coal companies further strengthened their rural “empires” by refusing to pay workers in US currency — preferring, instead, to print their own. Company scrip was exchangeable only at company-owned stores, which often carried a minimum of foods at prices high enough “to blood-suck the poorest widow,” as Mother Jones once said. One proud manager boasted that his company store was pulling down a higher profit margin from the workers than the coal.

But the principal workers’ complaint in West Virginia was the practice of local sheriffs empowering the companies’ private “detectives” as badge-carrying public law enforcement — the fact that private gunmen, often hired in big cities, were paid by coal companies to enforce both real and de facto martial law in workers’ communities of Southern West Virginia. A power to themselves, the private guards enforced anti-union organizing codes. As such, the so-authorized company guards were free to make arrests, detain miners indefinitely, sentence them in “drum-head” courts, dispatch routine disciplinary beatings and, sometimes, carry out political assassinations. (See Carla Rising, pp 37; 75-80; 126-27; 265-68) As I point out in the Afterword, the practice of deputizing private coal company guards was made illegal in WV in 1935, when the administration of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt carried out its widespread program of democratic reforms.

So, although Appalachian history is filled with examples of state and federal power intervening on the side of coal companies and their business associations, so much ink has been spilled portraying working-class people there as “lazy,” “unwilling to work,” or inherently violent. (This was a practice that began in the 1870s, when industrialists first “discovered” the region and its wealth of timber, oil and coal.) Taking a close look at the historical record indicates that working people turned to violence — picked up guns — more often than not, only after other, legal, democratic avenues for getting fair treatment and safe workplaces had been closed to them.

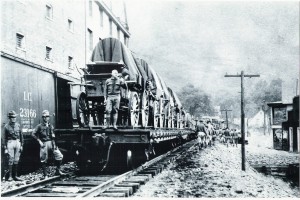

US Army occupying Logan County

(Source: Coal Country Tours)

As we watch today’s federal prosecution against coal company CEO Don Blankenship, many of us wonder whether the government’s approach is changing, with regard to energy companies — whether “King Coal” is finally being reined in, its worst offenders tried and jailed, just as so many of history’s labor activists have been. The history teaches us that there are likely other, new coal barons waiting in the wings to take Mr. Blankenship’s place. If so, they are easily recognizable today: Men who speak out in favor of Jurassic policies that are anti-worker, anti-union, and serve only to destroy the remnants of genuine community in Appalachia and elsewhere. It’s all-too-easy to imagine a future “business-friendly” administration, again deciding that bombs and thousands of “elite” gunmen are a good response to Appalachia’s “radicals” — actually a tired and angry underclass. (See Carla Rising, pp 157-65; 298-300)

Many of us hope, alternatively, that the federal government might take a different course than that of 1921; that it might launch new initiatives to protect all workers, to protect our land and water, and to build a new, more diverse, peaceful and sustainable business environment for the region and nation as a whole.

— Topper Sherwood,

Berlin,

November 2015

* Another thing that surprises me in my research: Very similar labor strikes and demonstrations were happening at the same time in Europe, in the wake of WWI and the Russian Revolution. And, once again — fearing a real out-of-control workers’ rebellion — fledgling social democratic governments often responded with guns, with tragic results.

** It is worth noting here that the 1921-23 presidency of Warren Harding was tainted by allegations of illegal transactions between the military and US energy firms. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teapot_Dome_scandal)