UK study: ‘Green Revolution‘ farming methods make Rwandan farmers poorer

High-tech Western agricultural may have succeeded elsewhere, but organizations that try to apply its high-production principals to African farms are likely doing more harm than good, according to a current university study.

Today, new “Green Revolution” programs have been trending through Africa, promoted by government agencies and private donors as “an essential response” to rising population, limited land and a need for growth to fuel more general development, according to Neil Dawson, the lead author of the study and a researcher at the School of International Development, University of East Anglia (UK).[pullquote align=”center” cite=”” link=”” color=”#00FF00″ class=”” size=””]

Participants were often forced to grow corn, despite their perception that their own traditional crops (sweet potato, banana, and taro) would be more productive and leave them less vulnerable to food shortages.[/pullquote]

The UK-based study involved long-term observation and contact between researchers and rural farmers in Rwanda. Published in World Development, the research was collectively funded by more than 50 universities and private foundations in the United Kingdom.

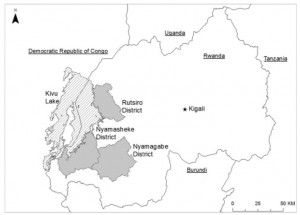

The study was conducted in eight villages across three sites in mountainous western Rwanda between October 2011 and June 2012.

The Western “Green Revolution” in agriculture has given momentum to numerous public policies that promote seed varieties and other technology-intensive tools to boost the production of marketable crops. Green Revolution strategies have transformed the rural economies of many Asian and Latin American countries between 1960–90, the study said, adding that the transfer of the same strategies to Sub-Saharan Africa has “had limited success.”

The strategy “is meant to raise farmers’ incomes, (and to) develop their countries’ economies and, by doing so, combat hunger and poverty,” Dawson wrote. “But there are good reasons to suspect that the impact of the policies have not all been favourable.”

In one example, researchers observed a stream of villagers carrying their sugarcane from the wet lowlands, where it grows best. They trade the cane with familiar marketers who offer potatoes in return, grown in drier soils and better able to resist frost. The image is used to show that crop selection and cultivation are based on a complex matrix of local knowledge systems, harvest conditions, familiar social patterns and trade networks, labor availability and “relations between villages and their inhabitants,” the authors wrote.

Increasingly, such systems are being replaced with government aid programs, designed to produce a single cash crop, such as sugar, corn or tea. Monocrops pose a host of problems, said the report.

First, said Dawson, conditions facing today’s African farmer are “very different from those in Asia some 40 years ago.” In that time and place, unlike Africa, small-holding landowners “could benefit more directly through favorable terms of trade and governments could even fix prices for them.”

Second, today’s policies are framed as a response to a crisis caused, in part, by traditional African farming methods that have been “unproductive,” the study said. Western practitioners arrive in African communities with the assumption that local people will benefit from technological and systemic “upgrades,” despite the subsequent eradication of their traditional knowledge and practices.

“As a result, the long-standing knowledge of soils, ecological gradients and associated social as well as economic interactions have, in a flash, been replaced with rules and administrative boundaries,” the author wrote.

Rwanda, study region. (Creative Commons license.)

Finally, the study concludes, exported Western farming policies represent “pervasive attempts to alter (farming as) a key feature to people’s lives” – potentially affecting “hundreds of millions of farmers across sub-Saharan Africa,” yet there is “startlingly” little assessment of their actual impact.

In conducting the study, the researchers spent many months talking to villagers in three mountainous areas in western Rwanda to ask questions and hear responses about important changes in villagers’ lives.

Ten percent of the study’s participants had seen the government repossess land that had been set aside for conservation or re-allocation to refugees. Others have seen “non-approved” crops destroyed by local officials, said the report. Penalties, it seaid, “are commonly handed out for not meeting standards set by a wide array of policies.”

Households were ordered by a government mandate, for example, to grow tea as a cash crop. Land use was firmly controlled in such areas, designated only for tea production. Seedlings were given to households, but required up to four years to reach maturity.

“At Nyamagabe, the most remote site, 30% of households had…been compelled to convert large areas of cropland to tea plantation,” the study said. Later, it said, public officials began to tell local farmers that all the remaining land would eventually be designated for tea production.

“(I)f a household proves unable to manage that land effectively, the government reallocates it, often without compensation…. Only a minority of wealthier households see this as an opportunity to accumulate (income),” Dawson wrote.

Participants in the study were often forced to grow corn (maize), despite their perception that their own traditional crops (sweet potato, banana, and taro) would be more productive and leave them less vulnerable to food shortages.

“The mono-cropping system is not good because, in the past, we would grow beans and cassava together,” said one farmer interviewed by the researchers. “You could take the bean harvest and eat them and also plant corn while the cassava was ripening. Then you would always have some food to eat. It was a good system. There were many different harvests we would get from that. But now, if you harvest beans, as soon as you have finished eating them you begin to suffer from hunger.”

Along with new methods, the risks are also foreign to African farmers. Modern seeds cannot be used without fertilizer, forcing them to borrow funds. Complying with the policy requires a leap of faith, which some take and a few succeed, the writer said. People’s incomes might actually increase, the study said, “yet they have become poorer, stripped of their most valued resource: land.”

“In contrast, 16% of wealthier households had been able to increase their holdings, their productive potential, and incomes,” it said.

To reduce poverty and hunger through farming innovation, the researchers recommend “working with poor farmers – not against them.”

“We do not advocate that traditional farming practice is superior to any form of modernisation or innovation,” the authors wrote, calling for “innovation and support that…targets the needs of rural smallholders, and involves their participation.”

Future programs and policies, said the researcher, “should be subject to much broader and more rigorous impact assessments” – especially in places where poverty is a factor.

“In Rwanda, that means encouraging land access for the poorest (farmers), and supporting traditional practices through a gradual and voluntary modernization.”

1. Green Revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications of Imposed Innovation for the Wellbeing of Rural Smallholders, by Neil Dawson, Adrian Martin, and Thomas Sikor. (Creative Commons license.)