The New ‘Melting Pot’

In November 1989, when the Berlin Wall came down, I called all the magazine editors for whom I’d ever written, and told them I was going to Berlin.

One of the publications that gave me an assignment was The Chronicle of Higher Education, which landed me in a big conference room of the East German Education Ministry, talking to five or six uneasy Communist administrators.

My questions were mostly about how the GDR’s national college system was going to change in the face of the newly opened border, with “decadent” Westerners coming and going – including some intrepid new university applicants. Already, the East German administrators could look out of their big frame windows onto the wide Karl-Marx Platz, to see groups of young East Germans handing out leaflets and putting up signs, promoting a whole new spectrum of unheard-of clubs, political causes and parties.

One of the administrators was a man who’d spent a year on a rare Cold War exchange program in Michigan. He volunteered an answer to my question.

“In the United States, you’ve been raised with a sense of tolerance for other people — people different than yourself,” he said, and I recall how he raised his open hands, in a sort of apologetic shrug.

“Here in East Germany, we are going to have to learn tolerance.”

Now, the infusion of more than half a million refugees from war-torn Syria and elsewhere is prompting Germans of all kinds to “learn tolerance” again. Today, in Berlin, we’re seeing blocks of standardized metal-box apartment buildings going up. They will house newly arrived thousands of fragile souls — war-weary men and women with their children. I stopped by one just a couple of hours ago, to watch the kids playing wildly on newly installed playground equipment. One was riding a bicycle in and out. Another — a real little guy — picked up sticks in the nearby woods.

We see these families all over town, stumbling through Berlin’s urban ‘multi-culti’ life. They’re riding the trams and buses for the first time, trying to figure out just which line to take, what buttons to push.

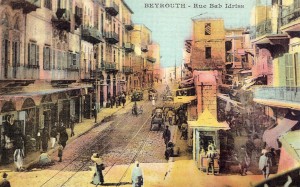

Beirut, Lebanon ca. 1900 (Credit: https://leelouzworld.wordpress.com)

Strangely, perhaps, I am reminded of the town where I grew up — Charleston, West Virginia — a destination for Jewish immigrants from bigger East Coast cities during the 1860s and 1870s, just after the American Civil War. These new settlers came, as I understand, at about the same time as another group, Orthodox Christians from Lebanon.

These families of wandering Jews and Lebanese settled and thrived together in my hometown. Later generations of Charlestonians patronized their shops and businesses which brought us groceries, clothes and dry goods, shipped from distant places.

Even as they faced 20th-century discrimination, their congregations were generous, joining with the Protestants and Catholics and donating to civic causes that gave food, shelter and counseling to the needy — to the poor and homeless — taking to heart the message of one Republican mayor I remember, who said:

“Our town will not be a good place for the well-to-do to live in, unless it’s a good place for all of us to live in.”

Germans do not often think of their country as a “melting pot,” but it is. In the years following the devastation of World War II, reconstruction here depended on a national program to recruit and educate “foreign workers,” many of them from Italy and Turkey. Between 1950 and 1960, the West Germans welcomed almost 260,000 such workers to help rebuild their country. Even more immigrants came to the West during the time that followed the 1960 closing of the East German border.

Certainly, Turkish-Germans have faced discrimination in Germany, and still do. Their influence here is substantial, however, and I suspect they will play a key role in helping today’s Middle Eastern refugees to fit in.

Those who work with the refugees tell us we cannot continue to see them as “mass victims,” as boatloads of “illegals” without faces, doomed only to land either in captivity or the bottom of the Mediterranean.

I’ve met one new Germany resident from Syria. He has a calm face, framed by a long beard, and a top-knot of hair. He’s unusually tall. Chatting with him, I learned that he had been an athlete in Syria. He’d played basketball there before escaping, over land. He told a harrowing story of getting into Europe — and about the tortures before his escape.

“Everyone worked against the regime,” he said, in a low voice. “And everyone suffered for it.”

He showed me his scars, where the electrodes had been placed.

“They went easier on me, because I am an athlete,” he said. “My friends did not have it so easy.”

We talked about basketball. He enjoyed discussing how the different national teams are trained and how they play — the Italians, the French, the Germans….

“What national team interests you the most, if you could play for one?” I asked.

“Spain,” he said, without much hesitation. “Spain has the best training.”

When we parted, I wished him luck in finding a team. I want to believe that any team will be lucky to recruit him.

There are, of course, Germans who do not welcome the strangers — just as many Americans, Hungarians, British or French would not. I’ve spoken with Germans, especially in former East Germany, who openly express fear of foreigners — Muslims and Middle Easterners — having gotten the full dose of negative images for so long. I’ve sat across the table from skeptical Germans who talk about these prejudices, which are fairly common.

I listen and nod, but then remind him that I’m a foreigner too; that I come from a country built by generations of refugees. The United States has opened its doors to millions of these, including German-Americans who fled at least six different periods of political upheaval and war in this part of the world between 1750 and 1945.

“Welcoming immigrants has been a good thing, for us,” I assure them. “America became a rich country in many different ways because of its diversity.”

It’s true. One way or another, the United States has drawn an amazing, broad spectrum of talent from foreign shores. Anyone who cannot see and appreciate this is missing a big part of what America means, historically.

“Your new immigrants will have talents and skills we can only imagine,” I tell my eastern German friends. “You can admire them, share their pride as they achieve things here, as they become creative musicians and writers or innovative builders…designers or goalies on your soccer teams….”

“My country became strong as a global melting pot,” I finish. “Now your unified Germany and new pan-European Union can become the world’s melting pot!”

(I have to say: It’s been extremely rewarding to see the smiles this raises from people on the other side of the table, people who are surprised at this new understanding of the United States, their former Cold War enemy, if not of Germany and Europe.)

It’s even more rewarding to see Germany taking strides to save the victims of long-standing hate, fear and war in the Middle East, forcing all of us to face our doubts, our prejudices and our own fears, as we build new tolerance.

I hope it pays off for everyone.