Heroes and victims in Western

entertainment media

We rented and watched two films during the weekend.

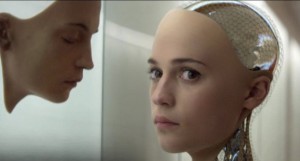

From Ex-Machina. Credit: Universal Pictures

Ex-Machina is a good modern Frankenstein (the book). The “doctor,” in this case, is a powerful tech-genius businessman whose sole motivation is manipulating the two other characters in the film: His seductive female android and a naive, vulnerable and utilitarian programmer/employee.

The second DVD we rented was Third Person about a writer trying to exorcise his demons via the dramatic fictional characters he produces on his Mac.

Like with so many others, these two movies had me thinking about today’s popular industry-made protagonists as cultural products. I would argue, that today’s film protagonists increasingly display characteristics not of heroes, but of victims — or, worse, of a person whose principal characteristic is his/her complete amorality.

I might also reference the current multi-Oscar nominee, The Revenant, although I don’t plan on seeing it. The reviews I’ve read make this much-praised product easy to dismiss as simple-minded alpha-male/vengeance-oriented “pain porn,” and supporting my point.

In these narratives, the ultimate “winner” is the person with the heart of stone and the most “transferable assets” — the most money, the best training, the fittest body and looks….

Conversely, I recall more classic heroes — people with more fortitude who made non-militant decisions from their desire (or need) to help innocent others or, perhaps, to send a message that doesn’t involve firing large numbers of bullets.

American protagonists increasingly seem to end up on top by closing their hearts and losing command of their “software,” the gray matter between their ears. They win either by brute force or by becoming manipulators of the clever, self-serving cheat. Their creators have them rise by setting aside what might be seen as old, outdated Western values; but they do so at the risk of sacrificing some basic human ones — with often ludicrous results.

How many politicians, openly or otherwise, admire the Machiavellian work of Kevin Spacey’s Frank Underwood? Do many rural Americans understand themselves in similar terms to the underpaid teacher in Vince Gilligan’s Breaking Bad, whose creator has said he wanted to take the character “from Mr. Chips to Scarface”? How many vigilantes are “educated” (trained) by video-game-like “heros” whose principal characteristic is quickly judging and executing “bad guys”?

This was one of my goals in writing “Carla Rising,” to come up with a non-violent response to our rapidly spreading sense of “victimhood.” Or, better: To show the negative outcomes of the too-easy, quick, reactive and violent response — even when that response seems completely justified.

In the end, of course, Carla Rising and her friends are not traditional heroes. If anything, the book’s surviving protagonists succeed not by their killing, but by melting into the social landscape. (I might also suggest that the “saving grace” of more than one Carla hero is not the capacity for violence, but for listening.)

Admittedly, one of my general role models for the work was Mario Puzo, who told interviewers he had chosen his characters for “The Godfather” — chock full of antiheroes — because these were people he knew from his own family. Stieg Larsson‘s characters were another touchpoint.

I also read the first volume of The Hunger Games, by Suzanne Collins, who — although clearly (wonderfully) satirizing today’s “reality TV” – cannot get around a heroine who does play (and excel) at the game, which is still-and-always killing innocents for others’ entertainment.

To put a point on it: Since the end of WWII, too many people have been recruited to fund and fight on one side or another in this or that real-life foreign conflict, with little or no genuine social or moral cause behind it. We have convinced a lot of young men (on all sides) that they can all be “heroes” by signing up.* History is filled with the story of the brave warrior who suddenly realizes he’s become something less than the as-advertised “freedom fighter” and closer to an expendable mercenary, a victim.

This is something I tried to do with Carla Rising — to question the moral implications and social costs of settling local problems by “hiring more police and jail guards.” Alternatively, I question the wisdom of setting aside our highest moral codes to go for the “quick and easy” solution — reaching for a gun — and making this look easy in popular media.

* I recall one early Iraqi “insurgent” who told his interviewer, “You think we are moved by Al Qaeda recruiting videos? No! Our model is Mel Gibson in Braveheart!